The Dopinglinkki net service is intended for fitness enthusiasts who use doping substances (also known as performance and image enhancing drugs, PIEDs/PEDs), their friends and family members, professionals from different fields who meet users of doping in their work, and all those interested in the effects of doping substances.

Doping and Public Health Conference in Helsinki 2026

Save the date! Dopinglinkki is organizing the next international conference on Doping and Public Health. The event will take place on June 11-12, 2026 and the preliminary venue is the Helsinki Central Library Oodi.

Anabolic steroids dependence

It has been estimated that up to a third of anabolic steroid users experience dependence. The dependence shows up as the chronic use of anabolic steroids at high doses and using multiple substances over a long period of time, despite the physical and psychosocial harm they cause.

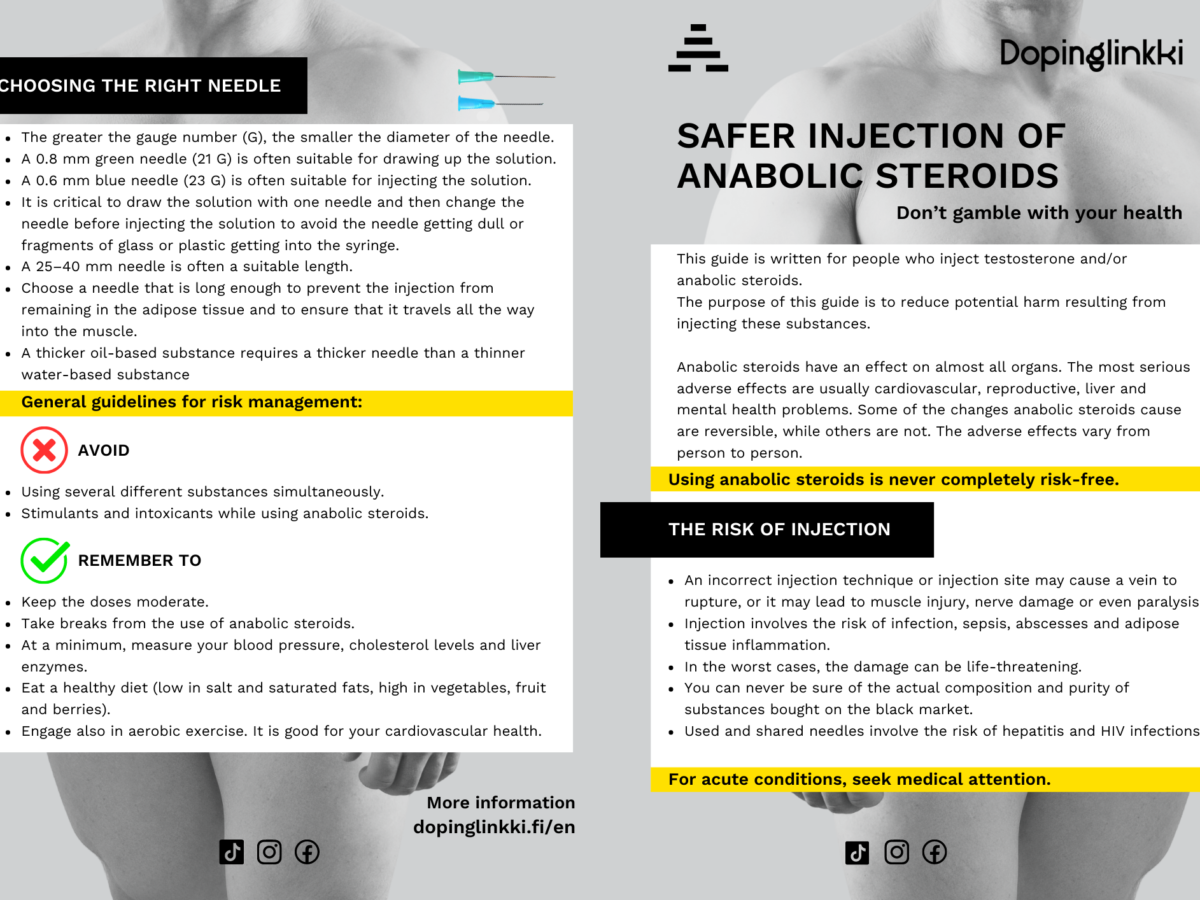

Safer injection of anabolic steroids

This article is written for people who use testosterone and anabolic steroids by injection and for health professionals who treat them in the course of their work. The purpose of this article is to reduce the potential harm resulting from injecting anabolic steroids.